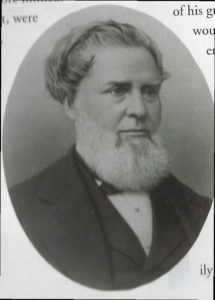

I came to know of guideboat builder Fred Burns through my friend Richard Dechene. Fred was Richard’s grandfather, who Richard and his cousins called “Boobah”. Fred was quite a fellow. He built a beautiful home in Long Lake at age 75. He then started building the first of 13 guideboats at age 76. Richard wrote this about him for Sulavik’s book The Adirondack Guideboat;

“…my grandfather was the type of man who kept everything and recycled it. My guideboat (built by Fred) has plywood decks. I believe all of his boats had them but I am not one hundred percent sure. He built thirteen guideboats , usually in the winter in his shop. His (builder’s ) jig was homemade using large wire spool ends for his circular ends and drilled holes through them so he could angle the boats however he wanted. His tools were always in great shape and very sharp. As a child I knew never to touch them. The handles were always varnished and commonly colored rings were painted around the base of them.

I think the most interesting thing about (my grandfather’s) boats was that they were totally built with hand tools. He owned a few power tools but rarely ever used them.

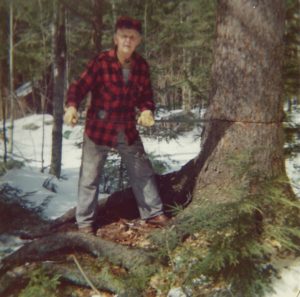

I can remember spruce stumps in the woods covered with canvas tarps. He prepared these so that he could cut his ribs from them with his cross cut saw.

My father would usually get the planks for the sides and grandfather would hand plane them into tapered boards. There were always piles of curly shavings on the floor which made a great fire starter.

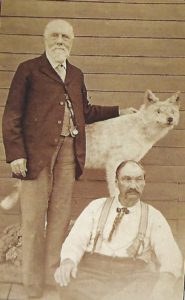

In the spring, launching day was always a big event for us. (Grandfather) would set his new boat on his homemade cart and pose for pictures. Then he would walk it to the town beach, about a quarter of a mile away, and launch it. He’d take it for a spin to see how it handled and returned to see if anyone else wanted to test it out. This was always fun for us.”

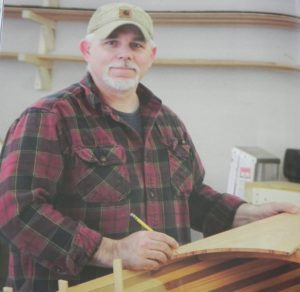

I was privileged to have access to family albums that contain photos of Fred building his guideboats. Here are some of the best showing him at work.

The stumps will be dug out of the ground and flitches cut for root stock.

Fred’s son gave him a chain saw but he preferred to use a cross cut saw and cut flitches by hand. Richard remembers hearing the monotonous “shish-shish’ going on for what seemed like hours as the flitches were cut. Richard’s house was close enough to his grandfather’s so that he could clearly hear the cross cut saw at work.

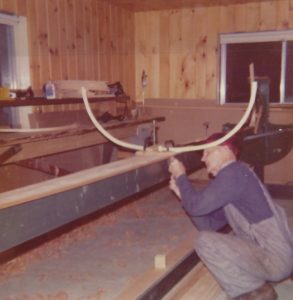

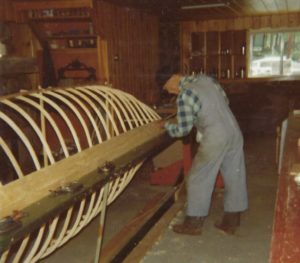

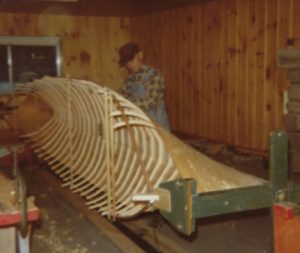

The flitches were allowed to dry for at least a year and then cut into ribs and stems. Here Fred fastens the ribs to the bottom board.

Planking was done using a rotesserie style builder’s jig.Fred’s guideboats employed seven planks per side rather than the usual eight.

Cutting off the nib ends of the ribs.

The deck

Then time came for the launching of Fred’s latest guideboat. The boat shown here was called Snow White because it was so light in color. It was built in the winter of 1978-1979 and was launched in July 1979. Since Fred was born in 1892 that makes him 87 when he built the Snow White. Here is Snow white on Fred’s home made cart built from salvaging items from the Long Lake town dump.

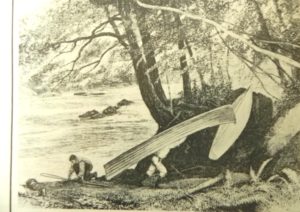

Arrival at the lake shore.

In she goes.

A trial spin.

Richard tells a rather amusing story about his growing up although was not very amusing from his grandfather’s point of view. When Richard was nine years old or so his Mom let him learn to drive. Every morning he would take the family car out for a prescribed route for a short distance from their house. It would end with Richard backing the car into the garage. On one occasion there was a guideboat on the floor of garage. Richard didn’t notice the guideboat. Car and guideboat had a tragic meeting. When grandfather Fred viewed the aftermath, an awful look came over his face, he turned on his heel and left. Mom and son felt awful. Richard thinks the boat was salvaged by fiber glassing it.

Richard tells me that a daily ritual for his grandfather every morning during the summer months was to trundle his guideboat down to the town dock. He would then row it up to the upper end of the lake about 8 miles away and back. Phew, hard to believe that of an 80+ year old. Not this kid!